The Baobab Story

The remarkable upside-down Baobab

by Joss Axmann

A 25-year-old French naturalist, Michel Adanson, was the first European to describe that “wooden elephant” in 1754, so the botanists later named this strange African tree “Adansonia digitata”, while the Arab traders originally called him(!) “bu-hubub” which finally became “Baobab”. The local people had given him different names, for example “Mbuyu” (Mbuyuni is the place of the Mbuyu) in the East African Kisuaheli-speaking region.

The African Baobab, famous as he is amongst botanists, can quite certainly not compete with the Californian coast redwoods as far as maximum heights are concerned. Age is still under discussion. Most now living Baobabs probably are not much more than 400 to 500 years old. Radio-carbon-testing of some large and obviously old specimens said 1000 years, while it is believed that 2000- or even 3000-year-old trees may be around somewhere). So height is about the only property where the Baobabs are definitely ranking second only amongst all the trees, because what they miss in height, they impress with trunk diameters of 11 meters and more.

Adanson wrote about him: “I perceived a tree of prodigious thickness. I do not believe the like was ever seen in any part of the world”. So when considering all the additional properties of the Baobab, even now many botanists regard him as the absolutely most extra-ordinary figure amongst all the trees on this

planet (and so do we on Mbuyuni Farm, and we are very proud of our magnificent choice pieces of Baobabs).

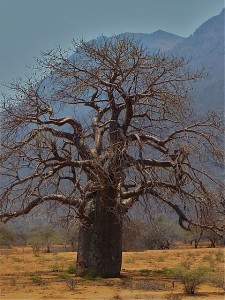

His outward appearance comes first: There are certainly no other trees which look as impossibly bizarre as the Baobabs. They are excessively “obese”, with short and very, very fat trunks, and with crowns consisting of a bundle of comparatively thin and crooked branches, the whole missing any sensible proportions we expect from an orderly tree. This rather ridiculous appearance resulted in a large variety of theories and legends amongst the various African tribes living with these strange trees. One of the best known of them runs about as follows:

When the Great Spirit created the world and finally arrived at making the various species of trees the Baobab was one of the last ones constructed and – learning by doing even then – he turned-out to be by far the most beautiful specimen amongst all the trees. But the Baobab happened to be an extremely vain character hopelessly lost in self-

admiration, and – driven by quite unjustified discontent – he soon started to complain bitterly about a number of negligible mistakes the Creator had made when designing him.

This of course annoyed the Unfailing tremendously, and in a sudden fit of anger He personally pulled the Baobab out of the ground along with his roots, and with His super-natural force thrust him back into the ground up-side down, so that the shaggy and pitiful roots were now in the air and the truly beautiful crown down in the ground. And the trunk in the process had become very short and at the same time laughably fat. And this is why the “Upside-down-

trees” ever since are looking so ridiculous.

But what matters outward appearance compared with inner values? In fact, the Baobab is quite outstanding as far as his usefulness is concerned. Elephants and other animals feed on it, and practically everything from his top to his bottom had found good use by the people living with him in the olden times and has even to-day. The nourishing young leaves are used like spinach or dried and made into a powder used for cooking. The pith in the big seed-pods, somehow reminding of styropore, is rich in vitamin C and B1 and Calcium, and the bean-shaped seeds embedded in it contains 15% oil. Roasted they make a substitute for coffee, while the hard husks end-up as containers and vessels, and powdered they sometimes replace tobacco (which possibly is healthier than real tobacco).

The Baobab’s wood is in fact no real wood, but kind of a spongy, comparatively fibrous matter. His smooth grey bark which resists bush-fires is very thick and quite hard outside with

strong and coarse fibers underneath which were (and are) used to make dresses, mats, roofs, baskets, nets, ropes and so on and so forth.

During the rains an old fat Baobab can store for the dry saison several cubicmeters of water in his spongy trunk, and his diameter is accordingly growing a couple of centimeters. The clever (and thirsty) elephants open his trunk with their tusks and feed on the moist fibers. Sometimes they hollow out the whole trunk, and people have then used the trees as reservoirs to store water, as grain-stores, stables, even as tombs (and sometimes to lock-up evil-doers).

The roots supply a red dye, the bark tannin, and the smoke from burning the dried pith is said to work as an insect repellent. And so on and so forth on a long list.

The Baobab’s white or creme-coloured 24-hour-blossoms – large for a tree – are exquisitely beautiful even when later drying on the ground. Their smell, however, attracts only those animals – mainly bats – which are responsible for the tree’s reproduction.

Not unexpectedly the Baobab also supplies medicinal preparations supposed to help against dozens of maladies from ordinary fever to smooth skin for babies and even to malaria. As in many other cases there is still no clear scientific evidence as to the effectiveness of those home-brewed mixtures, but some – at least if assisted by strong confidence – probably are helpful to a varying degree.

No wonder that many Africans tribes venerate the Baobab, look at him as the seat of their gods, of the souls of their ancestors, of spirits important to them, and in

many villages which are often located around an impressive old Baobab, the elders have taken weighty decisions since time immemorial. Consequently, in many African regions the Baobab is strictly “untouchable”, and only a lightning or old age would one day bring him down.

After all, the Baobab is indeed something very extra-ordinary, upside-down or not.